This story is a part of Picture’s December Revelry challenge, honoring what music does so properly: giving individuals a way of permission to unapologetically be themselves.

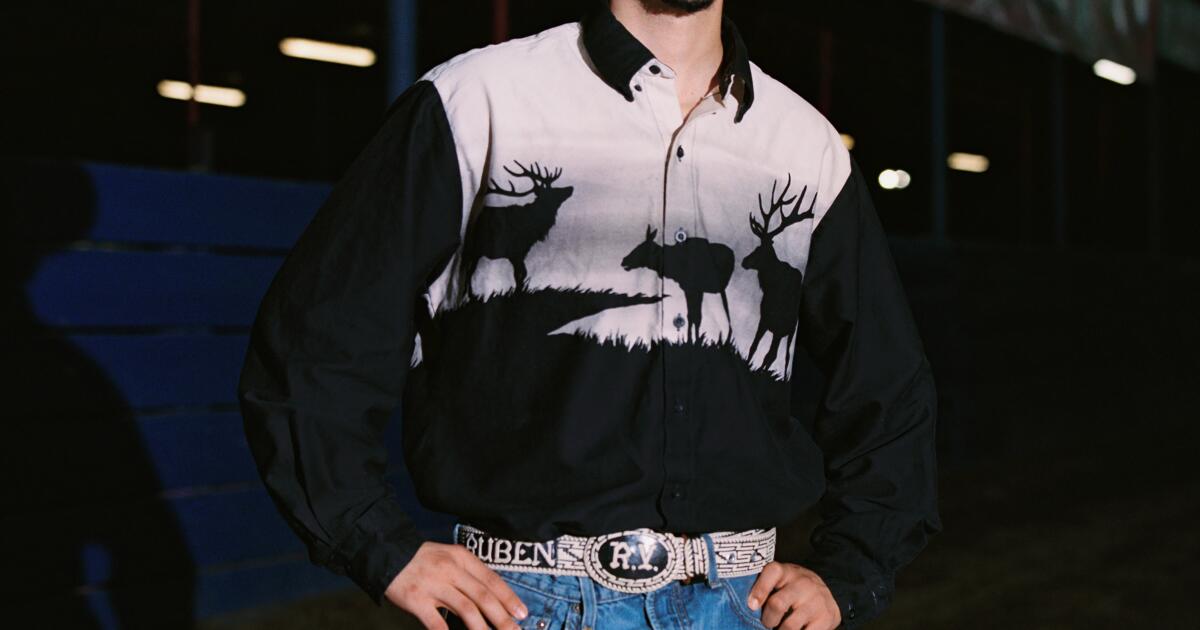

The belt used to belong to his father. Black leather-based, silver stitching, “RUBEN” spelled throughout the facet with the initials “R.V.” on the buckle, for Ruben Vallejo, a reputation each males share. Now it sits on the waist of the youthful Vallejo as he will get prepared for an evening out on the Pico Rivera Sports activities Enviornment, a spot he’s been to “over 50 occasions,” he says, however this one’s particular. He tucks in his thrifted button-up shirt, adjusts his belt buckle and appears within the mirror.

For the Vallejo household, the world is a second residence and dancing there may be custom. It stands as a cultural landmark for Los Angeles’ Mexican neighborhood, internet hosting a long time of concert events, rodeos and neighborhood celebrations. Vallejo’s dad and mom first began going within the early ’90s, when banda and corridos started echoing throughout L.A. Tonight, the beloved crooner Pancho Barraza is performing and Vallejo goes together with his mother, sister, aunt and godmother.

Vallejo wears a black tejana from Marquez Clásico, a thrifted vaquero-style button up, thrifted denims and a belt handed down from his father.

At 22, Vallejo doesn’t see música regional Mexicana as nostalgia — it’s merely who he’s, one thing he wears, dances to and claims as his personal. “I need to revive this and let different individuals know that this artwork and tradition continues to be alive,” says Vallejo. “From the way in which that I costume, from the music I take heed to, I need to let all people know that the youngsters like this.”

It’s a bit of previous 6:30 p.m. on a Sunday in late October, and the sound of a stay banda carries from a small Mexican restaurant close to the Vallejo household’s Mid-Metropolis residence as the joy for the evening builds. The horns and tambora spill into the road because the neighborhood celebrates early Día de los Muertos festivities. Inside, Vallejo opens the door to his storybook bungalow, the place his dad and mom lounge in the lounge. But it surely’s his bed room that tells you who he’s — an area that appears like a paisa museum.

Thrifted banda puffer jackets dangle on the closet wall: Banda Recodo, Banda Machos, El Coyote y su Banda Tierra Santa. Stacks of CDs and cassette tapes line his dresser, from Banda El Limón to Banda Móvil and a signed Pepe Aguilar. On one wall, a small black-and-white watercolor of Chalino Sánchez he painted himself hangs beside a framed Mexico 1998 World Cup jersey. “Every little thing began with my grandpa,” Vallejo says. “He was a trombone participant and performed in a banda in my mother’s hometown in Jalisco.”

Music runs within the household. His uncles began a bunch referred to as Banda La Movida, and Vallejo continues to be instructing himself acoustic guitar when he’s not apprenticing as a hat maker at Márquez Clásico, crafting tejanas and sombreros de charro.

“I really feel like being an previous soul provides individuals a way of how issues was again within the day,” he says of the intergenerational bridge between his work and private pursuits. “That connection is one thing so wanted proper now.”

Past the banda memorabilia, the actual story lives within the previous household images — snapshots of yard events, his dad and mom in full ’90s vaquero fashion in L.A. parking tons and a big framed portrait of his uncles from Banda La Movida, posing in matching blue jackets and white tejanas.

“It is a image of us within the [Pico Rivera Sports Arena] parking zone. We’d go to help my cousins in a battle of the bandas. Which additionally meant fan golf equipment in opposition to fan golf equipment. The pants had been much more saggy then,” explains Vallejo’s mom, Maria Aracely, in Spanish.

Vallejo’s search for the evening is easy however intentional: a black tejana from Márquez Clásico, a thrifted black-and-white vaquero-style button-up patterned with deer silhouettes, unfastened “pantalones de elefante,” as he calls them, his dad’s brown snakeskin boots, and, after all, the embroidered belt that ties all of it collectively.

“That is very Pancho Barraza-style, particularly with the venado shirt. I regarded up previous movies of him acting on YouTube. I do this loads with these older banda appears,” Vallejo says.

A country leather-based embroidered bandana with “Banda La Movida” stitched vertically hangs from his left pocket — a memento his mother held onto from her brothers’ group again within the day.

Operating fashionably late, Vallejo arrives at Barraza’s live performance with lower than an hour to spare, however he appears unbothered. His mother and older sister, Jennifer, are there, alongside together with his aunt and godmother. A mixture of mud and alcohol hangs within the air because the household makes their means throughout the pretend grass tarps masking the decrease degree of the world. Barraza is onstage with a mariachi accompanying his banda. With the quantity of individuals nonetheless out ingesting and dancing, it’s exhausting to consider it’s previous 10 o’clock on a Sunday evening.

Strolling previous the stands, Vallejo’s mom is in awe as she factors out a sure higher degree part of the world and recollects the quantity of occasions she would sit there and see numerous bandas earlier than she had Ruben and his sister. Because the live performance nears the tip, Barraza closes with one among Vallejo’s favourite songs, “Mi Enemigo El Amor,” which Vallejo belts out, jokingly heartbroken.

“I hadn’t seen him stay but and the ambiente right here feels nice as a result of everybody right here is linked to the music. Despite the fact that we’re in L.A. this appears like residence, like Mexico.”

Frank X. Rojas is a Los Angeles native who writes about tradition, fashion and the individuals shaping his metropolis. His tales stay within the quiet particulars that outline L.A.

Images assistant Jonathan Chacón